- Home

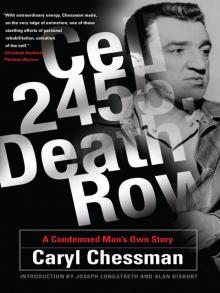

- Caryl Chessman

Cell 2455, Death Row Page 10

Cell 2455, Death Row Read online

Page 10

Of one mind, they walked quickly to the car. “Well, lookee here,” Bobby said. “Do you see what I see and are you thinking what I’m thinking?”

“I’m thinking,” Virginia replied, “that my feet are getting tired. I think I feel like riding for a while.”

“In that case,” Tim said, still playing the tough guy, “quit gabbing so much and get in. Let’s go for a ride.”

“Yeah,” Whit said, almost soberly, repeating Tim’s words, “let’s go for a ride. Let’s go for a ride to Hell. I’ll do the driving.”

Whit shoved Virginia over and got behind the wheel while Tim and Bobby scrambled into the back seat. Whit, whose dad had taught him to drive their pickup truck, eased the sedan from the curb. Then he honked the horn in one long, continuous blast until the portly owner of the car came running from the drugstore^ shouting! at them. Then Whit sent the sedan speeding off.

Virginia moved over in the seat. She pressed her leg against his suggestively. She tuned the car radio to some dance music.

Then she asked, “Which way is Hell?”

Whit knew she was trying to make fun of him. He didn’t intend to let her get away with it. Having the powerful car under his control wrought a change in him. It opened up, with alcohol’s help, a new world, a world a man could conquer and do widi what he pleased.

“I’m not so sure which way Hell is,” he said, “but I’m looking for street signs now.”

Virginia laughed in a sly way. “I know a shortcut in case you’re interested,” she said, and pointed to an intersection up ahead of them. There sat a cop on a motorcycle, watching traffic. Whit tensed; fear pulsed through him. He wanted to disappear, to hide; but he couldn’t. He had to keep going, to act natural. With an effort, that is what he did. He was “walking” forward into danger.

The cop didn’t impress Virginia. When Whit made the boulevard stop, his heart in his mouth, Virginia waved at the cop and the cop waved back, then not paying any more attention to the car or its occupants. Virginia said, “The stupid bastard.”

Then she spoke to Whit, “Did the big bad policeman scare you, little man?”

“No,” Whit said, anger taking the place of fear. He had to show her he wasn’t afraid; he had to show himself that, too.

He pushed down on the accelerator. The car leaped ahead, around a corner, onto the open highway. The speedometer needle climbed. The windows were open and the wind roared in their ears. Whit shot through a stop sign and Virginia wasn’t relaxed any more.

Behind them a siren screamed faintly.

Tim shouted, “What the hell’s the score?”

“Virginia’s in a hurry to get to Hell,” Whit shouted back. He fought the big, sleek sedan around an S-turn. Then he pushed the gas pedal down to the floorboard. For a half mile the car continued to pick up speed. Two motorcycle cops were after them, gaining on them. The speedometer read eighty, eighty-five. They were approaching a jammed intersection. Whit kept his foot on the accelerator. Virginia screamed and made a grab for the steering wheel. Whit cursed and shoved her away. He knew, then, he would get through; he had a reason. Virginia could be scared, too. He had the power to scare her.

Somehow a space opened up for him at the intersection and he got through, not expertly, perhaps even miraculously, but he got through. He turned onto a side street, then another. He had ditched the bulls, as Tim called them.

This premise came from the experience: If you used your head and your guts, you could do what you wanted and get away with it. The premise lit up in his mind like a neon sign, and suddenly Hell took on a special allure of its own.

Whit laughed, even though his body was trembling and his hands on the steering wheel were wet with perspiration. He had to hide his own physical reaction.

“Don’t ever grab at the wheel again,” he told Virginia. “I know what I’m doing.” He tried to sound tough.

“You were just lucky,” Virginia said. She wouldn’t give him any credit. That made him angry.

“Yeah? Well, let’s see if I can be lucky again.” He swung the sedan around in a U-turn, headed it toward the main highway again.

“Never mind, little man,” Virginia said. “I’ve got a date. And my date’s got his own car and plenty of money. He’s not just a half-pint show-off who’s been living in some screwy dream world.”

Her words hurt him. They cut like a knife. He had to get over that. He had to reach the point where nothing anybody said could hurt him. He didn’t get a chance to reply.

Tim said, “What the hell!”

Bobby was giggling. “I wet my pants,” she said, making a joke out of it.

“I’ll be damned!” Tim said, and then he laughed. They all laughed. They weren’t drunk any longer; they were cold sober, and they were having a reaction and trying not to show it.

“Where do you want to be left off?” Whit asked Virginia.

“At Bobby’s. I’ll show you how to get there.”

When he stopped in front of Bobby’s house, he had already thought out what he wanted to say to Virginia. “I thought you were going to show me a short cut to Hell. What’s the matter, change your mind?”

“You’re too little, little man. I don’t think they’d let you in,” Virginia said, composed again.

“I don’t think they could keep me out,” he said. “The whole damn bunch of them couldn’t keep me out.”

Her eyes were cat’s eyes. They measured him contemptuously. “Meet me at the malt shop tomorrow after school and I’ll make you run back home to mama, yelling for help.”

Whit nodded; then he drove off, fast. Tim climbed over the back of the front seat, slid down and lit a cigarette.

“What do we do now?” he asked.

“You going home?”

“Hell, no,” Tim said. “Not until my old lady cools off.”

“I’m going home in the morning, not tonight. I’ve got some business to attend to tonight. And the first thing we better do is get rid of this crate. Every cop in the country will be looking for it.”

Tim said, “You don’t sound like the same guy.”

“I’m not,” Whit said. “The guy you knew before this morning is dead.”

Tim laughed. “Sure,” he said, “and the guy I met this morning will be dead too before the day’s over if he doesn’t slow down.”

Whit whipped the car into the curb. “I’m going to keep going, Tim, and I don’t intend to slow down. If you want to get out and walk, now’s your chance. If you want to come along with me, that’s good; but remember we’re going at my speed.”

“Hell, don’t be so damned touchy. I’m with you, sure; only it’s just hard to believe one guy could change so much so damned fast.”

Whit grinned. “You ain’t seen nothing yet.” Whit knew he had to push himself; he had to keep going and he didn’t dare look back.

That night he stole two more cars and committed diree burglaries. Early the next morning he and Tim had breakfast in an all-night drive-in. The loot from the burglaries had been hidden at the cabin in the hills. The cash had been divided equally and was in their pockets.

“I’m going home for a while and then I’m going to meet Virginia,” Whit said. “I’ll take the Ford and you take the Buick, and I’ll meet you here tonight around six.”

“Got ya,” Tim said. His voice as well as his walk had a swagger in it. “But you better watch out for Virgie. That broad is dynamite. And she’s hotter than a two-dollar pistol.” He was one man of the world talking to another. His fox face was animated.

Whit returned home. He hadn’t any more than stepped through the front doorway, and closed the door behind him, when his dad asked him where he had been. He didn’t answer the question. He walked around his dad and entered his mother’s bedroom.

“Hello, Whit,” she said. “You’ve come home.” She didn’t accuse him. She didn’t make a scene. If she had it would have been easier. He saw her face was haggard, but she was smiling. His dad stood behind him, saying nothing, b

ut full of things to say and waiting for the chance to say them.

“Did you find my note?” Whit asked.

“Yes,” his mother said.

“Was Barbara’s family here?”

“Yes.”

“The cops?”

“No.”

“Reverend . . .?”

“No.”

His father broke in. “Now that your mother has answered your questions,” Serl said, “don’t you think you owe her some explanation?”

Whit looked then at his dad. Serl was a shell of his former self; life had beaten him down.

The rebellion flared in Whit’s mind and it hardened him. His dad had taught him that honesty is the best policy. His mother had taught him that they were God’s children. They, his parents, were good and decent and honest beyond dispute, and yet look at them. Oh, God, look at his parents! At that moment Whit would have battered and smashed anyone who might have suggested to him his mother and father would be rewarded in the next world. After this, the very idea of it seemed the vilest cruelty imaginable. Why, why had they been so wantonly treated for being good and decent and honest?

Whit told himself: It’s because they are good. That is the terrible truth. The good are defenseless.

“I asked you a question,” Serl said.

“I know,” Whit replied. “I heard you. I’m not sure how to answer or explain. I’m not sure I could. Or should.”

His dad stiffened.

Whit said, “Maybe it’s just that I’m fed up with poverty. Maybe I just feel like having some fun for a change.”

His dad began to lecture him angrily. “I would think, at least for your mother’s sake, that you would . . .”

Whit refused to listen. He would have walked out right then, but his mother stopped him. Her helplessness and her goodness stopped him. She told him she was sorry for their poverty and that she and his father would try to make him happier.

That was what Whit hated most—the vicious irony of it. His mother was willing always to take the blame, forever was she thinking only of him. Better she should hate him.

His mother continued talking to him and he almost turned back. But he couldn’t and wouldn’t turn back to fear. He had to prove there was no need to be afraid. He had to combat cruelty with cruelty. He had to give God a chance to destroy him, and the Devil too. Most of all he needed to be strong. Right then nothing else was important.

He began to wheeze.

• 9 •

Conquest, and the Wall

Whit paid another visit to the parsonage. “Hello, Reverend,” he said. “How are you?” His smile was broad, boyish, disarming, seemingly carefree.

“Come in, son. Do come in,” the minister said, and his own countenance perceptibly brightened. “It’s good to see you smiling again. Can it be that my prayers for a satisfactory solution to your problem have been answered?” The minister looked optimistic.

“My problem?” Whit said. “I haven’t any problem, Reverend.”

A puzzled expression appeared on the man of God’s face. He reminded Whit gently, “But the other day . . . you told me . . .”

Whit frowned, simulating perplexity. “Me, Reverend? I told you something the other day? Oh, no, Reverend; you’ve got me mixed up with somebody else.”

The minister was patient. “Saturday morning last. You were here. You were definitely here. And you told me—” Then followed a disturbingly accurate account of what Whit had told him.

Whit’s face hardened and all expression went from it. “Have you told anyone else what you just told me, Reverend?”

“Why, no. I told you I wouldn’t.”

Very softly, Whit spoke the question: “Reverend, do you think you could prove I was here and that I said what you claim I said?”

The lean frame of the minister stiffened. He took a step forward. “See here, young man: what do you mean by that? Exactly what are you getting at?”

“I’ll tell you what I’m getting at, Reverend. It just happens that I don’t remember coming to see you. I don’t remember telling you anything. So if anyone asked me, that’s exactly what I’d have to tell them. I’d have to tell them that you must have been dreaming. And that’s a pretty bad story to be telling on somebody, Reverend. I think my folks have enough problems already without having that story of yours being added to them. So if I were you, I wouldn’t tell it unless I could prove it, Reverend. I’d forget it.”

Whit turned on his heel and walked out. He didn’t bother to close the door behind him. He didn’t bother to look back. He knew the preacher was probably standing there watching him, perhaps with his mouth agape.

Whit thought viciously: Well, let him pray for some more guidance. He needs it more than I do now.

Being cruel to be kind wasn’t an original idea. Hamlet had heeded that same injunction. But Whit wasn’t concerned with literary analogies or comparisons. He was interested in burning bridges, in being sure no avenue of retreat was left. Less than two months in the future, a kindly policeman would warn him: “Sonny boy, keep on like you’re going and you’ll wind up in the gas chamber.”

And where was he going? Why, to Hell, of course. So to hell with the gas chamber.

Whit walked into the malt shop and looked around. Virginia was sitting in a booth on the left. Whit was disappointed because she wasn’t alone. He had wanted her to be alone and waiting for him. Instead, a couple of boys were with her, and the three of them were so engrossed in their own conversation they didn’t notice Whit. He sat on one of the stools at the fountain and ordered a Coke. Sipping the Coke, he started to think, but that was the last thing he wanted to do, or dared do. He swallowed the rest of the Coke with one gulp, set the glass down, spun around on the stool, and looked straight at Virginia.

She saw him. She smiled a quick, mocking smile. “Well,” she said, “if it isn’t the little boy!”

He walked to the booth and stood looking down at her, ignoring the two boys, not smiling, hiding the fact her words had stung. “Yesterday,” he remarked, “it was little man, and I haven’t shrunk any since.”

She looked at him and laughed hilariously. The boys with her laughed too.

Whit stood there, embarrassed and angry. His face felt hot. His eyes took in every detail of the sinuous girl: the hair, the white, strong teeth, the cat’s eyes, the full, red mouth, the ivory column of neck, the casually worn sweater. Too, the knowing look, worn as offhandedly as the pancake makeup, and the animal animation. A blatant advertisement of an available commodity, and a psychological cannibalism. Perhaps the male spider suspects that the female intends to eat him as soon as she has mated widi him. But at least Mr. Spider has an excuse for what he does. Whit had no excuse and he wanted none. He had only a reason that was obstinate and arbitrary. So he stood still and said nothing.

Virginia stopped laughing. “Something on your mind, little boy?” she asked, but the laughter remained in her words.

“I want to talk to you,” Whit said.

“You want to talk to me?” The incredulity was obscene and feigned.

The skinny boy who kept trying to paw Virginia snorted and played the game with her. “He wants to talk to you!”

“I guess he wants to give you some fatherly advice,” said the other boy, the one who resembled Mortimer Snerd.

Virginia’s reaction was instantaneous and savage. She turned on Mortimer Snerd. “You shut your goddam smart mouth!”

Snerd was the picture of shocked and injured innocence. He looked at his skinny friend with a now-what-did-I-say look. Skinny could only shrug.

Unsmilingly, Virginia stood up, shoved Skinny out of the way and brushed past him. She sunk her fingers into Whit’s left arm and said, “I need some fresh air.” Then she propelled Whit out the door of the malt shop. Under her breath she was saying some very uncomplimentary things about Snerd. Her choice of language was not judicious, and her anger amounted almost to mania.

“Have you got a car?” she asked.

/> Whit nodded he did have. He pointed to an immaculate tan ’34 Ford coupe at the curb. “I found it last night in a used-car lot.”

As he was pulling away from the curb, Virginia took a cigarette package and matches from her sweater. Out of the corner of his eye, he watched her extract the last cigarette and light it. She gave the match a flip out the window. She inhaled the smoke deeply into her lungs. Her hands were trembling slightly. Then she slowly closed her left hand on the empty cigarette pack, crushing it. This done, she threw it from the window.

“Drive fast,” she said. “Drive crazy fast.”

He speeded up.

“Faster! Lots faster!”

He whipped the light Ford through the city traffic, then out onto the highway, heading for the hills. He came close to killing them both several times. Neither of them cared.

Whit parked on an abandoned road high in his hills, near the cabin he and Tim had built. “Well, here we are,” he said, settling back in the seat. The wild ride had left him keyed up, expectant. And one part of his mind was still trying to comprehend Virginia.

She stretched luxuriously, and yawned. A smile played at the corners of her mouth; her green eyes were boldly appraising. “You’re crazy, little boy,” she said.

Whit’s smile lighted his young face for only an instant. Those green eyes boring into him could have been ten thousand years old. He would have to ignore them. “Thanks,” he said. “Maybe it won’t take me too long to be crazier.”

“I don’t know about you,” Virginia said, “but I could go crazy a lot easier if I had a cigarette and something to drink.”

Whit didn’t let his smile reach his lips, but he let it radiate through him. Proud of himself he said, “In that case, you aren’t going to have any trouble at all.” He pushed open the door and got out. “Just a minute,” he told the girl; “I’ll be right back.” He walked to the cabin hidden in the trees, selected three cartons of cigarettes from the loot he and Tim had hidden inside. Then he followed the trail to the reservoir; from the cold waters he extracted a green bottle, more of last night’s loot. He returned to the car, indulging in a grin of pleasure. Fear was a tyrant and he was committing an act of tyrannicide.

Cell 2455, Death Row

Cell 2455, Death Row