- Home

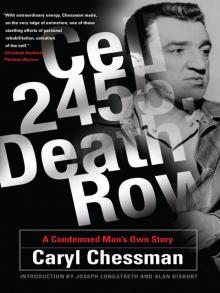

- Caryl Chessman

Cell 2455, Death Row Page 3

Cell 2455, Death Row Read online

Page 3

Then, on May 26, Chessman’s New York publishers, Prentice-Hall Inc., announced they would publish Trial by Ordeal on July 7—just four days before Chessman was scheduled to die.

It appeared Chessman had outwitted the state again. While there was some speculation initially that the manuscript to be published might not be authentic, such speculation was firmly squelched in short order.

Chessman’s literary agent, Joseph Longstreth of New Tork, said, “I have an exact copy of the original Chessman manuscript of Trial by Ordeal held by Warden Teets, and if Teets desires I would be most happy to fly out there and compare it with him, page for page, line for line, word for word.” Teets declined to make this comparison. That ended that. There was no doubt that the manuscript was the real thing.

But how had Chessman managed the “impossible” feat of smuggling the bulky manuscript out of the maximum security confines of San Quentin’s death row? During an exclusive interview, Chessman cleared up the mystery. “When I read that Clarence Linn had said the manuscript could be destroyed, I had to talk with another convict. He may or may not have been a condemned man.” [Chessman spoke in hypothetical terms and refused to name names.] “I must protect the man at all costs.” He did say that there were “five or six” persons involved in the complex scheme and that it was “strictly a convict deal.”

Chessman said he turned a carbon copy of the manuscript over to convict No. 1 in three separate installments and “it might have gone out [of Death Row] in some trash.” Convict No.l turned it over to convict No.2 who was told to hide it within the prison while Chessman waged a legal battle to get the original manuscript released.

For many weeks, Chessman said, the manuscript was hidden in one or another of the prison shops, and it changed hands frequently. A crisis finally arose, he said, when the inmate then guarding it was suddenly changed from one job to another. “He apparently decided the best thing to do was to get the manuscript entirely out of the prison,” Chessman said.

Asked how was this accomplished, Chessman replied: “A minimum security prisoner could have left it lying around and bypre-arrangement an outsider could have picked it up and mailed it.”

Chessman added, “Every day it becomes more apparent how apt a title I picked. I had to fight to stay alive to complete the book. Then I had to find a way that everyone said didn’t exist to protect the book and get the manuscript of it to my publisher and agent. Now I am obliged to combat the efforts of certain self-righteous citizens who are determined to destroy the book’s potential. They aren’t going to succeed.”

It was a sign of his rehabilitation that he did not turn his rancor against those who imposed restrictions upon him; he honestly understood their position. Did they understand his? Did they comprehend, in human terms, what it meant to Chessman, alone in his cell, lights out, to know that having finally achieved something worthwhile in his life, having at last, tortuously, given meaning to an otherwise meaningless existence, he was to be denied the right to continue his efforts? Had the Chessman writings deserved the condemnations of the individuals involved, one might have understood; had the Chessman writings been vitriolic attacks on officials or the system of penology in California, or had they been replete with falsehoods and twistings of truth, one might have understood. As it happened, the reasons for wishing to silence Caryl Chessman were never made perfectly clear. Could they have been? The truth has not yet been told. But that these attempts to silence him were unlawful has been made clear.

Here, again from these unpublished, self-penned “interviews” with himself, Chessman wrote about the suppression of his second book, Trial by Ordeal:

Halfway through Trial by Ordeal, Chessman was jarred to learn that California Director of Corrections Richard A. McGee had banned all publication of all writings by a doomed man.

“I couldn’t believe it at first,” Chessman recalls.

But it was true.

The reason given by McGee: “Invariably books written by condemned men involve their own cases. Consciously or unconsciously they are designed to influence people about the man or the case.

“Under present law, however, cases involving the death penalty are never finally adjudicated until the man is executed. We therefore felt that there should be no attempt made to influence the public as long as the case is pending.”

Second, even if it were true, reporters can interview any doomed man they desire and quote him at whatever length they desire, wherever and whenever and however they desire. What is the difference whether the condemned man’s published words about his case are intentionally spoken to a reporter or written down by the man himself on a typewriter?

Third, what Mr. McGee really means when he says that “no attempt [should be] made to influence the public as long as the case is pending before the courts,” is that no attempt should be made by the doomed man, but that anyone else can say anything they want any time they want. Obviously Mr. McGee has neither the authority nor the ability to silence any citizen, lawyer, public official, groups, crank or crackpot who deserves to have something to say about the doomed man or his case, whether pro or con.

“Another result,” McGee has stated, referring to the ban, Ss that if a [condemned] makes money from a book, it permits him to employ legal talent to fight his case, which other prisoners can’t afford.”

This may be a noble sentiment in the abstract, Chessman replies, but it also is an ominous one in reality. What Mr. McGee actually is contending for among the doomed is an equality of poverty, helplessness and anonymity. In effect, he is conceding that the state can execute and execute quicker and easier if the condemned man is fund-less, friendless and helpless, an advantage which he seems to feel the state should have. Mr. McGee, in consequence, is also saying necessarily that he is willing to use the naked power of his office to keep the state’s doomed broke and silenced. Why?

Press reactions to Caryl Chessman, as a writer, were astonishing. In some instances they were frightening; in some instances sickening. I recall particularly four different members of the fourth estate who talked to me at great length about Chessman as a writer. Each decried his success, attributing it to sensationalist publishing, to the linking of promotion to impending executions. In actual fact, considerable restraint was exercised on the part of everyone concerned in the publication of Caryl Chessman’s works; it would have been simple enough to sensationalize the publications. As his literary agent, I turned down many exploitative offers to milk my client’s notoriety. The works of Caryl Chessman did not need artificial stimulation in that fashion; the press itself provided more than enough sensationalism.

In the instance of these four particular reporters, each one derided the “literary merit” of Caryl Chessman’s books. In two instances, however, I discovered that the people voicing such condemnation had not even read Chessman’s books; and in the other two cases under consideration, both had written unpublished books themselves, without having received so much as a sympathetic letter of rejection from a publisher!

It has always been sad, to me, to receive letters from hopeful or would-be writers saying, “Guess you have to kill somebody, be a reformed alcoholic or drug addict, or get on Death Row before you can write a book anybody will publish!” The lengths human beings will go to to deceive themselves! And this sour attitude, too, helped cloud appreciation of Chessman’s quality as a writer.

It would be impossible, of course, to divorce the Chessman case and the Chessman “situation”—i.e., his Death Row life and the sideshow aspects of his life-and-death struggle as painted in the press—from his literary efforts. But can we divorce any writer, of any genre, from his environment? Shakespeare? Cummings? Faulkner? Dickens? Rilke? It is the essence of futility to speculate on whether or not a given artist would perform—or would have performed—differently under different circumstances. The two can never be separated, and attempting to do so serves little purpose.

The unpublished works of Caryl Chessman were not available for

study until after his execution. In most instances, they reveal a struggling writer, an author of undisciplined talent who has not yet found what he wants to write about. And it is no criticism to say that Chessman wanted and needed to write about himself. That he did, and was encouraged to do so, is a fact for which the psychological and penological worlds, society itself, can be eternally grateful—and for which the future will give credit to those to whom credit is due. That concerted efforts were made to suppress Chessman, once he proved he had abilities, will always remain a subject of discussion and suspicion. The real motive can only be guessed.

Caryl Chessman wrote several short stories, some of which remain unfinished. Some are attempts at humor. Most are forced and contrived, for he was writing from the head, not the heart. Some of the stories tried to portray emotional experiences, to convey the meaning of death, of life, of frustration, depression, exaltation, humiliation. Again they do not meet with complete success. They are forced and artificial. But when he wrote about justice, his words burned with fierceness and truth. And when writing of his companions on Death Row, of their frustrations and foibles and peccadilloes, his words touched—even wrenched—the heart.

I have often been asked: “What effect do you believe Chessman’s writings had upon his case?” I am not being evasive when I respond that only history can presume to judge. We can, however, hazard several guesses.

It is unquestionably true that, had it not been for the Chessman books, there would not have been the national and international outcry over the agonizing stays of execution, the seemingly interminable legal battles, and the eventual execution of Caryl Chessman. It was his own writing which turned his case into a cause celebre. Perhaps we should say that it was writing which brought the confusions of the case to the awareness of the public. People took sides because his writings aroused them, one way or another. The public cared because they imagined they knew a great deal about the case. The press, in turn, played the “condemned author” game to the hilt, without regard, in many instances, for the facts involved. People still sometimes say to me: “Well, after all, he was a killer!” The sad truth of this shocking affair of twelve years is that he was not a killer. No life was ever taken—except Chessman’s! And it remains true that, with the publication of his second and third books, and his fourth, almost coinciding with his execution, the press took less and less of a searching look at the writings and more and more of a sensationalist view of the spectacle.

As the public sensation caused by Chessman’s first book subsided, his fate became more important than what he really said as a writer. It could be argued that Chessman failed as a writer, given the relative weakness of the second and third books and their inability to sustain the excitement of the first. But such a view ignores the fact that the three books—Cell 2455, Death Row; Trial by Ordeal; and The Face of Justice—were conceived as a trilogy and written as such. However, each stands alone, for the writer Chessman did not fall into the trap of assuming that every reader had read his previous books. But inevitably, much of the most “glamorous” portion of the searing story had been told, and books two and three demanded more of the reader than had book number one. Neither can one ignore the strained circumstances under which the second and third books were written and published. In actual fact, in the subsequent books, the writing itself improved. Chessman achieved restraint, acquired more finesse and polish, though he had still not shed himself of fiery tendencies which often overstepped the boundaries of need. He had learned much from those reviewers who honestly criticized his writing.

Yet it is important to remember, always, Caryl Chessman’s world was a singularly lonely one—lonely for one who had become a thinking, sensitive man. One has but to read the descriptions of his fellow Death Row inhabitants to know the caliber of this individual who was generally available for discussions and exchanges of ideas. How frustrating it must have been for a man of Caryl Chessman’s capabilities not to have stimulating minds to combat, with which to exchange thoughts and explore searching problems. Even the prison authorities, considerate as some of them were at times, were no match for the keen penetrations of Chessman, the observations of which he was capable, even the wit he often displayed.

Chessman’s own reactions to the press are often expressed in his books. He knew the tendency to slant, the evident willingness to publish half-truths and mere semblances of fact, and the constant pressure under which reporters were forced to produce their stories. Not many human beings ever have the occasion to know firsthand, as did Chessman, how fact can be distorted in order to make a better story. The almost constant refusal of most of the press to be explicit, to state simple truths, was a source of never-ending exasperation for Chessman. And yet, ironically, few figures of notoriety—or infamy— have been as open and forthcoming to the press as Chessman was, even to those who had taken him to task in print.

Again, it was of significance that the press chose to emphasize the smuggling of his manuscript out of the prison, rather than its content. Almost nowhere, even in literary circles and publications supposedly devoted to the well-being of author, publisher, bookseller, did one read editorials or even articles or little news briefs to the effect that something was wrong with the suppression. And the protests from abroad, if reported at all, only brought snide comments that foreigners should mind their own business. Where, in print, was the law prohibiting Chessman from writing seriously challenged?

Few men autobiographically have been able to bare their souls as dramatically as did Caryl Chessman in Cell 2455, Death Row. With swift strokes, he creates a dramatic narrative that stuns the reader, and it is a rare reader who does not have the sense of “There, but for the grace of God, go I”! But it is equally true that, once many have finished reading the book, they begin to rebel. I have known several people who could not finish the book. They said: “It’s evil, and the man is evil.” Better they should have looked into their own soul with equal tenacity and fearlessness to dissect their own weaknesses.

Of singular significance is the fact that Caryl Chessman never asked, and certainly never begged, for sympathy, or even for understanding. There are those who condemn him because, at the last minute, he refused to compromise his soul by hypocritical “acceptances.” Such persons are, in reality, seeking to assuage their own sense of guilt and fear. Caryl Chessman wrote as he felt and believed, the devil take the hindmost. He placed responsibility upon the reader, where it rightly belonged—on the public. Indeed, the very ending of Cell 2455, Death Row crystallizes the essence of Chessman’s dilemma:

Night soon will be here,

For me, it may be a night that will never end.

Does that matter?

Do your Chessmans matter?

The decision is yours.

It is obvious that one cannot divorce Caryl Chessman, the condemned convict, from Caryl Chessman, the published writer.

And it is equally obvious that Caryl Chessman, the writer, will have his day, long after those who executed the condemned convict have passed into oblivion.

* * *

Editor’s Note: This essay, written around 1970 by Joseph E. Longstreth—and published posthumously here for the first time—has been updated and completed by Alan Bisbort, author of “When You Read This They Will Have Killed Me”: The Life and Redemption of Caryl Chessman, Whose Execution Shook America (Carroll & Graf, 2006).

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Lo, how men blame the gods! From us, they say, comes evil. But through their own perversity, and more than is their due, they meet with sorrow . . .

Thus spoke Zeus, the father of men and gods, through the mouth of Homer.

To understand the evil of one man is to understand the evil of all men. For evil has but one root, but one cause, but one purpose. If they hope to survive, men of good will must learn this lesson soon and well: Evil seeks but the opportunity and the means to destroy itself; only when frustrated and denied its birthright does it turn with savage violence against its tormento

rs.

Today a dreadful dagger is pointed at the heart of Christendom. And from within a many-faced evil swaggers at noonday, strikes swiftly and terrifyingly during the midnight hours. Our label for this internal evil is Crime.

We know that there are those who walk among us who seemingly are not of us. And because some of them rob and hate and kill and throw away their lives we call them children of the Devil. Quite often they regard themselves as such. But we, as well as they, are wrong, and when we wreak blind vengeance upon them we do a futile and a tragic thing. Unwittingly we seek to propitiate a malignant god whose goal is to rob us of our humanity.

A familiar proverb tells of a blind man who, coming to a wall, declares himself to be at the end of the world. From diat proverb is drawn my book’s pervasive theme—even a society with excellent vision sometimes has a perverse and tragic tendency to follow the example of the blind man.

I asked myself: Why?

Cell 2455, Death Row is an earnest effort at an answer.

I feel impelled to add that the book has been written for one purpose only—because its author is both haunted and angered by the knowledge that his society needlessly persists in confounding itself in dealing with the monstrous twin problems of what to do about crime and what to do with criminals. Pled, consequently, is the cause of the criminally damned and doomed. It’s time their voice was heard. And understood.

Caryl Chessman

San Quentin, California

PART ONE

FACILIS EST DESCENSUS AVERNI

• 1 •

Death by Legal Execution

Thursday afternoon, October 30, 1952. Death Row.

Cell 2455, Death Row

Cell 2455, Death Row