- Home

- Caryl Chessman

Cell 2455, Death Row Page 5

Cell 2455, Death Row Read online

Page 5

We’ve entered the Big Yard on a weekday morning a few minutes after the two mess halls have disgorged their small army of break-fasters. The yard seems to bulge with prisoners of all sizes and shapes, each garbed in blue work shirt, jeans, a jacket. Soon they will be on their way to work. The hum and babble of a thousand, two thousand, three thousand voices swells from this concrete canyon, speaking with a collective phonology of its own. Overhead a lone sea gull darts and squawks.

With a hundred briskly-taken steps we’ve crossed this, the northern end of the yard. We enter the North block rotunda, leaving the sun and the sky and the bright cheeriness of the new day behind. An old man with a wrinkled face and watery eyes looks at us incuriously as we enter. He is the doorkeeper of the rotunda, an ancient inmate who has seen so many come and go. He knows where we are going, but, after all, that is none of his concern.

One of the officers escorting us punches a button on the rotunda’s far wall; next to the button are two massive steel doors set one against the other. Both are manually locked and unlocked from the inside.

An eye peeps at us through a slot in the innermost door. The effect is momentarily comical, reminiscent of speakeasy days when the password was “Joe sent me.” Then we recall where we are and where we’re going, and we’re no longer amused.

The two ponderous doors are swung open—one inwardly, one outwardly—by the owner of the peeping eye, who proves to be a plumpish gnome with a wide and disarming, somewhat vacant grin. This grinning gnome is a trusty; faithfully, but with malice toward none, he guards these “gates” against interlopers—an incongruous, grinning Cerberus. Yet, strictly speaking, the gnome is really no guard at all, for no one covets access to the dread place above.

In we go, pausing with our escort as the gnome goes briskly about his business of closing and locking the doors behind us. Closed and locked behind us too are all the reassuring sounds, sights and smells which filled our senses a moment before. Too swiftly have these sensory impressions been blotted out.

His doors locked, the gnome tugs twice on a bell rope to signal our coming. From above, we hear a bell clang twice. With only slight assistance from our now stimulated imagination, the elevator cage to which we’re guided assumes the appearance of a gaping maw. Flanked by our escort, we ascend, in this gnome-operated cage, the equivalent of five floors, and step out, to the left, into a cramped, caged area.

According to a local wag we are now as close to Heaven as we will ever get; and, for a fact, the only direction one can go is down. That is where the gnome goes. The elevator door clicks shut; gnome and cage disappear.

From behind a bulletproof glass window set in a thick, rivet-warted steel door, the face of the correctional sergeant in charge of the unit is visible, slightly distorted by the poor refractive qualities of the glass. In front of this door is another, a screen-meshed, sliding one. Both, like those opening into the rotunda below, are locked and unlocked from the inside.

Our identity visually established (a phone call has notified the sergeant of our coming), these vault-like doors are quickly opened and we step within and halt. Behind us doors slide and slam; locks snap closed. To our left, in a “gun cage,” an armed guard alertly watches us. To the right, commanding a view of the entire length of the building on this side, is the sergeant’s office, the control and nerve center of the unit. Adjoining the office is a compact kitchen, and next to it a clothing room.

We’re searched. Trained fingers probe our pockets, run along our body down to our ankles, look in our footwear. Then we enter a steelbarred, multi-locked, double-doored enclosure resembling a huge bird cage, are passed through with a jangle of keys and a sliding of bolts, and, still under escort, walk some two hundred feet along a corridor fronting a row of cells and a shower stall. There we find Cell 2455. Its front is steel-barred, steel-slatted, designed for maximum security. Across the top of its door is a “safety bar”; when locked in position, this bar prevents the door from being opened, even when unlocked. On each side of the cell the walls jut out two feet into the corridor. The cell’s interior is functional, almost sterile, containing only a wooden table and stool, a sink and a toilet attached to the back wall, a cot and a board shelf above the cot which holds, neatly arranged, permitted articles and books. A set of earphones, with a ten-foot cord, hangs by a headband from a jack securely bolted to the back wall.

The safety bar across the top of the cell doors for the lower or far half of the cells away from the sergeant’s office is under the control of the armed guard who patrols behind a barred and screened walkway that runs the length of the corridor fronting the cells. When signaled to do so by our escort, the armed guard pulls the lever at the west end of the corridor and just outside the fenced-in area. Up goes the bar. One of the officers unlocks and opens the door. He motions us to enter. We step within. The door is shut, locked. With a squeak, the safety bar drops back into place.

There we are.

That, physically, is how we get to and into Cell 2455. Getting permanently out of the cell and living to tell about it, once having been lodged therein as a guest of the State of California, presents an infinitely more difficult problem. Considerably more than a few dozen odd doors, locks, bolts, bars, gnomes and armed guards stand in the way.

Cell 2455, you see, is a death cell.

And . . . Whit is in Cell 2455, twice doomed.

Whit is a broad-shouldered, 190-pound six footer in perfect health and physical condition, a trained and functional fighting machine who has survived the rigors of almost six years on Death Row. His appearance bears eloquent testimony to the life he has lived. His brown, wavy hair is cut short and is beginning to thin in front. His lips have been smashed almost shapeless, and his nose is battered and broken. He wears a four-tooth bridge; the teeth missing were knocked out. Scar tissue has formed above the alert hazel eyes which glitter when he’s angry, and there are innumerable turkey tracks beneath and beside them. His forehead is corrugated; his chin, scarred. An old injury to his left leg causes him to walk with a combined limp and bounce which is noticeable but which does not prevent full use or the leg.

By the most charitable standards, his face is not handsome or es-thetically pleasing. It is a face that has seen too much, a young-old face, scarred by violence. With its broken, humped nose, its washboard brow, its glittering, gold-flecked eyes, and when alerted to danger its aspect of bold, the-consequences-be-damned insolence, it is a predatory face that seemingly has found its rightful place in the gallery of the doomed.

Yet further observation reveals a disturbing quality about it which suggests the paradoxical duality of its possessor, for it is a face capable of grinning disarmingly, of laughing in great good humor, and when comically split by a grin or crinkled by laughter it becomes a homely, friendly face, devoid of ugly or fearful physical connotations. At those times, one realizes that much has been superimposed upon Nature’s original design, that violence, hatred and rebellion have remodeled it to suit their harsh, brutal fancies. Apparent, too, is the fact that its owner is wryly amused by its present, unlovely appearance. He remembers it was once a young, sensitive, wholesome face.

What changed it—and him?

That was long, long ago.

What brings a man to Death Row?

• 3 •

The Twig

It was 1921, a fine late spring day. May 27.

The war in Europe had been over for almost three years. And had not that war been fought to end all wars?

The third decade of the twentieth century had not yet begun to roar; the bleak, depression-ridden thirties were undreamed of. Fortunately, dreamers do not dream black dreams.

And Hallie was a dreamer, at heart a poetess with both feet firmly planted on the ground and her soft, searching blue eyes in the heavens. This day her most cherished dream was to be realized.

It is on this day the life and story of Whit begins—at Saint Joseph, Michigan. It begins unheralded in an unpretentious but sturdy house on a

quiet residential street. In the front bedroom a young, reddish-haired woman is in labor. This is Hallie, the gentle Hallie, destined to suffer so much and to die so terribly. The soft cries occasionally escaping her lips are involuntary, for her heart sings a joyous song. Soon she will have brought her first child into the world, and the pain is therefore nothing. She resolutely closes her eyes and clenches her teeth against it. . . .

The pain receded. When Hallie opened her eyes she saw the good Dutch countenance of the lady doctor, who would deliver her baby, looking smilingly down upon her.

“Well, Hallie, we’re all in readiness for the new heir.”

Hallie nodded happily. “Serl? Is he . . .?”

“Like all fathers. Fidgety. Keeps getting in the way.”

The tiny, silver-haired old lady standing at the head of Hallie’s bed was Hallie’s foster mother, a God-fearing Baptist who saw the whole of life in terms of duty to her Maker.

The pain stabbed at Hallie again. She clutched the edges of the bed and gritted her teeth. She cried out, then moaned softly.

Delivery proved complicated. The woman was so small, the child so relatively huge! And so obstinate!

Hallie fainted. Mother Cottle wrung her hands and began to pray aloud.

The doctor spoke sharply to Mother Cottle. “There’s no time for that and I’m sure He understands our problem. Now, quickly, do what I tell you!”

This courageous lady doctor who was Hallie’s friend redoubled her efforts to deliver the infant. She threw herself into the task like one possessed or inspired. She kept Mother Cottle hopping.

For long minutes the life of both Hallie and her unborn son hung in the balance. Providence was playing a familiar game. This time it ended on a note of triumph.

“Now I have you, you fat little rascal!”

The lady doctor held the newborn babe aloft by his pudgy legs.

Later Hallie opened her eyes. “I’m fine,” she insisted weakly. “And so is he.” She indicated the sleeping bundle snuggled in her arm. “Yet I must admit I didn’t expect him to be so big.”

“Judging from the size of him now, I predict he’ll be a six footer when he’s full grown,” the doctor said.

“Really?” Hallie said. This was wonderful news, for there hadn’t been a six footer on Serl’s side for generations. Of her own parents and ancestors, Hallie knew nothing. She was a foundling who had been legally adopted and raised by Mother and Dad Cottle. Hallie added, “And my little man is going to have several brothers and sisters.” Already the agony of giving birth had been entirely forgotten.

The doctor frowned but said nothing. She was unable to bring herself then to tell Hallie that she could never bear another child. I must wait to see if possible complications develop and pray they do not.

No complications developed. Hallie quickly regained her strength; she was soon back on her feet. When told she could have no more children, she did not become sad. Surely, she thought, this fat, jolly, golden-haired little man was enough. She was inexpressibly thankful for him. She took him in her arms and assured him of this time and again.

Late November was dark and cold; an icy wind whipped in from the lake. California, with its promise of sunny blue skies and golden opportunities, beckoned Hallie and Serl. Hallie especially was certain that her Whit was not a winter’s child. So they came west to the Golden State and established residence in the booming Los Angeles area. They found a cottage on Greensward Road which suited them ideally.

The seasons rolled around and all went well for this little family. The gentle Hallie lavished on her toddler the love and affection she herself had never known. They were great and inseparable pals, these two. Whit’s dad, too, was his pal, and romped with him each evening on returning home from the studio where he was learning to make moving pictures.

Almost from the hour of his birth, Whit gave evidence of precocity. When he should still have been crawling in his play pen, he stood upon his fat, sturdy legs and began to walk. When his vocabulary should have been limited to gurgles and coos, words spilled intelligibly from his delighted lips. Hallie found him trying to make out words in a book and taught him how to play a fascinating game called reading, and another called writing. When given a set of crayons and some paper, he needed no encouragement to begin drawing pictures, and they were very promising pictures for such a tot.

Serl laughingly referred to his son as “The Little Professor.” The nickname was an apt one, for Whit was a keenly inquisitive boy, anxious to learn.

From Hallie, Whit came to know God. God was the wise and good Father; they were all God’s children. God looked down upon them and protected those who sought and needed His protection. God expected them to help one another, to be kind and good to one another, and to find and pass on, in the way in which each was best qualified, the beauty and the meaning of life.

Whit and his dad tinkered and made things together. Whit was particularly fascinated with the family car, a Star coupe, and what made it run. Gravely he listened to his dad’s simplified explanation of the principle of the internal combustion engine. On the boulevard nearby was a garage; Whit made friends with the two mechanics and they let him go down in the grease pit with them. They let him “help.”

Hallie had an inexhaustible supply of exciting children’s stories at the tip of her tongue. In the evenings, after supper, Whit would curl himself up in his mother’s lap, and listen with rapt delight to the adventures of Peter Pan or Alice or Jack who had climbed the beanstalk. There were stories from the Bible too.

Weekends and vacation time the three had great fun together. There were trips to the ocean where, with tiny pail and shovel, Whit discovered wonders in the sand. Then the happy boy would stand and listen to the booming roar of the surf.

“It’s talking, Mommy!” he would exclaim delightedly. “The ocean’s talking to me!”

And Hallie would smile; she would give thanks to God that her sturdy son was aware that Nature could speak to those who would listen.

Whit was three and a half, going on four, and it was the Christmas season of the year 1924. The family purchased a huge tree for the front room and he helped his mother decorate it. The tree was a wonderful, dazzling sight. That evening, after they had lit the candles on the tree and turned out the living room lights, Whit listened, wide-eyed, to his mother’s recitation of the visit of St. Nick. Later, Hallie and Serl heard him in his room, apparently talking to someone. They looked in upon him.

Whit had his teddy bear propped up in front of him and was reciting to Teddy, word for word, “ ’Twas the night before Christmas . . .”

They exchanged startled glances. So far as they knew, Whit had heard the poem but once!

Returning to the living room, Serl chuckled. This was not the first time his son had shown an ability to remember practically everything he heard or read or saw. “The little professor is some guy,” he said approvingly.

Hallie’s gentle face wore a worried frown. She said, “Sometimes I’m afraid for him, Serl.”

“Afraid? In the name of creation, why?”

“I’m not sure I can put it into words. Perhaps it’s nothing more than a feeling or a premonition.”

Serl wasn’t a complex man and he strongly resented even the suggestion of the presence of fear in his household. Further, it wasn’t like his wife to voice such thoughts. That the boy was smart as a whip was certainly no cause for alarm as far as Serl was concerned, and he told his wife so.

Hallie smiled and said agreeably, “You’re probably right, Serl.”

She loved her husband and her son quite as much as she loved life. Actually they were her life, and her loyalty to both was fierce, unqualified. Yet there was a loyalty she owed to her dream and it need not conflict, she thought, with her loyalty and devotion to her husband and son. When she was younger, there had been creative fire in this small, plain-faced young woman. It had been a need and a demand. She had wanted to write, to be a poetess; yet, the two who had adopted and rai

sed her—and another, near-blind child—had stifled her desire.

So, under this pressure, Hallie had channeled this creative fire into secretarial work and had become a competent and skilled private secretary to a man who had forged a multimillion-dollar business empire.

She had done this and waited. Then she had met Serl. And Serl had given her a new life. Her dream hadn’t died, yet it no longer was hers alone.

There was a meaning and a beauty to be found, to be set to words or to music or on a canvas, and from the day of his birth, Hallie had never wavered in her conviction that her son would one day find and express in his chosen way this meaning and beauty. Hadn’t her toddler heard and understood the voice of the surf? The knowledge was as frightening as it was wonderful, for it told Hallie that her little man would suffer and be sad and often walk alone. But this was not too great a price to pay for what would then be his.

• 4 •

The Twig Is Bent

Winter came, and with it days of fog and rain. Whit caught a cold; when he began to sniffle Hallie wanted to keep him home from school, but he begged his mother to let him continue. Against her better judgment, Hallie gave in to his plea. Then school was out for the Christmas vacation. The cold had stayed widi Whit. He ran a light fevei. But his spirits were so buoyant his mother found it almost impossible to keep him in bed. She gave him the run of the house. Then, when the rains let up briefly, she permitted him to go outside and play with his small friends. After a few minutes he found his breath coming in short gasps.

“Let’s rest,” he said, and usually he was the last one ever to want to rest.

“Sissy!” diey cried.

So Whit played all the harder. He returned indoors chilled through and through and wheezing. His fever rose. He became dizzy, then nauseated. He had to fight to breathe.

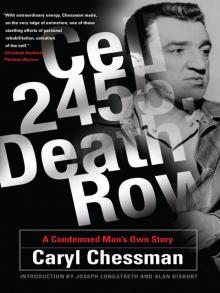

Cell 2455, Death Row

Cell 2455, Death Row