- Home

- Caryl Chessman

Cell 2455, Death Row Page 6

Cell 2455, Death Row Read online

Page 6

By the time Serl got home, Hallie was frantic. They dressed Whit in his warmest clothes, bundled him in a blanket and drove him to the family doctor. Serl had telephoned ahead and had been instructed to bring Whit to a nearby hospital where the doctor would be waiting.

On the way to the hospital, Whit began to turn blue.

“I can’t breathe, Mommy!” he cried. “I can’t breathe!”

Then Whit lost consciousness. He appeared to stop breatfung.

Hallie looked in horror at her son. “Oh, God, Serl,” she cried, “hurry! Hurry!”

The doctor was waiting. Whit was placed on a table in minor surgery and the clothes from his upper body were stripped off. The doctor plunged the hypodermic needle directly into Whit’s heart. The adrenalin did its lifesaving work swiftly. Whit’s eyelids fluttered. He recognized his parents and smiled wanly. He began once more his fight to breathe. They took Whit to a private room. They put him in an oxygen tent. He got worse, lost consciousness and began repeating over and over the simple child’s prayer his mother had taught him:

“If I should die before I wake . . .”

“Frankly,” said the doctor, “he hasn’t much chance.”

For forty-eight hours, Hallie and Serl kept a vigil at their child’s hospital bedside. The torment of watching this small son hang precariously between life and death was almost more than they could stand. Pneumococci were rampaging in both of Whit’s lungs; as well, his bronchial tubes were inflamed and clogged. When the doctors attending Whit despaired of his life, Hallie prayed with a quiet, intense desperation.

“Dear Lord, please don’t take our son. Let us keep him.”

Whit lived, and Hallie gave the credit to God.

By the time the crisis had passed, Whit’s body was thin and his face sunken. Brought home, he spent many days abed, as many more indoors. Physically he was a pathetic caricature of his former chubby self.

One day, his eyes sadder than usual, he stood watching his mother. “I’m sorry, Mommy,” he said. “I’m awful sorry for all the trouble I caused you and Dad.”

Hallie cried. She couldn’t help it. Impulsively, with the tears running down her cheeks, she took this little man of hers in her arms and held him tight.

“Don’t cry, Mommy,” Whit begged. “Some day I’ll be big and strong and then you won’t have to worry about me any more.”

Whit returned to school just as winter was reluctantly giving way to spring. There, with paints, paper, cardboard, glue and imagination, he made a “present” for his mother. He wanted to make her happy again.

The wind blew up a rain. Whit didn’t want the rain to spoil his present so he took his heavy coat he had worn to school and covered the present. He was hurrying home when an older boy came along on his bicycle.

“Hi, Louie,” Whit called out. Louie lived down the street from Whit and before Whit had gone to the hospital Louie had often ridden him around while he delivered his paper route.

“What’ve you got there?” Louie asked, braking his bike to a stop beside Whit.

“This,” Whit said. He lifted his coat so Louie could see. “I made it for my mother. Do you think she’ll like it?”

“She sure won’t like you getting yourself all wet just when you’re starting to get well,” Louie said. “Hop up on the handlebars and I’ll give you a ride home.”

Whit perched himself on the handlebars of Louie’s bike, still clutching his present with one hand. A car suddenly came skidding around the corner, going too fast. Six or seven high-school students were piled inside. Louie had to swerve sharply to avoid being run over. He and Whit took a bad spill. The teen-agers laughed loudly and kept going.

Louie snatched little Whit from the rain-swollen gutter. The latter looked like a drowned thing, but he still clung desperately to his present, which was in a pitifully bedraggled state.

Louie got Whit home as fast as he could and explained to Hallie about their accident. Whit was shivering. While his mother stripped off his wet clothes, he tried not to cry over the loss of his present. He had wanted so much to make his mother happy with the present, and now it was ruined. He began to wheeze and Hallie had dreadful visions of losing this only and beloved son. As soon as she had Whit out of his wet clothes, dried off and in bed, she called the family doctor, imploring him to come as quickly as it was humanly possible.

With the passing minutes, it became increasingly more difficult for Whit to breathe. His thin chest heaved violently as he gasped for breath. He had to sit up to get air into his lungs.

Then the doctor came. Whit was promptly given another shot of adrenalin, this one being injected into his arm. The shot relieved him sufficiently to allow fitful, labored sleep. He slept sitting up in bed.

Whit had bronchial asthma. For years to come periodic attacks would subject him to a hellish torment. Apparently they were brought on by a combination of overexertion, damp, cold weather, dust or certain pollens and hairs (especially from some animals), his state of mind contributing to the severity and duration of an attack.

Hallie and Serl tried every remedy. The doctors agreed Whit would probably “outgrow” the condition. Meanwhile Whit was given medicines, put on special diets. During attacks, a tent was built around him and various preparations were burned.

Whit’s initial reaction to these attacks had been one of fright. Fortunately, his parents hadn’t babied him or revealed their own fears. When Whit had asked, “Mommy, what’s happened to me?” his mother had told him, in a matter-of-fact way, that his asthma was a result of weakened lungs; in time it would go away; meanwhile she and his father would do everything possible to help him get well; he should have trust in them, be brave and pray to God to be cured; and he must never think for an instant they loved him any less because of his asthmatic condition.

This condition acted as a governor on Whit’s physical activities. Being an extremely active little boy physically, he soon discovered the price he must pay for overexertion. In a way he couldn’t explain, he regarded his asthma as a thing of personal weakness and even of shame. The need to be strong became more demanding with each passing attack; it lurked in his mind and overpowered reason. Yet, on the surface, he remained a friendly, shyly happy child.

Hallie and Serl moved several times in the next few years, seeking a climate less irritating to their child’s hypersensitive lungs and bronchial tubes, as well as a community where Whit could find new friends and interests, where he could grow and, so far as possible, be a normal little boy. At length they settled in Pasadena. Whit was then seven, thin, wasted and short for his age. The asthmatic attacks seemed to be stunting his growth.

Whit lost no time in falling in love with the district. Almost at the front door of his home, the Flintridge Hills rose steeply, abruptly; to the north, not far away, were the majestic Sierra Madres. Even as a sickly slip of a boy, the nearness of the hills and mountains awoke something within him, and when he was troubled and physically able he would go alone high into them and stand and look down.

Although he remained small and not strong physically, Whit improved tremendously in his new environment. The law of compensation had begun to assert itself. The foundations of Whit’s world had been shaken because he had been; the realization, without being thought out, came to him that only he had changed: there was still an order and an unshaken centrality outside himself.

Whit did exceptionally well in school. He made friends with all his schoolmates. Hallie arranged for him to receive private tutoring in French. Each day was an adventure.

As it should, the classroom led Whit away from the classroom. An-nabelle was an exquisite, imperious creature Whit’s own age. She stirred Whit profoundly. She first deigned to notice his existence one day at recess. The other youngsters were busily and noisily at play. Whit stood apart and watched, and doing so he was watching and apart from himself as well—a short, brown-eyed, tousle-haired lad in search of a dream with a special meaning.

Annabelle marched over to h

im. “Why are you looking at me like that?” she demanded. “You’re always doing it.”

Whit was startled. At the time he hadn’t even been aware of An-nabelle’s presence. It was on the tip of his tongue to say so, yet spontaneously he said something not less truthful but more satisfying to his beautiful questioner. “I was daydreaming, I guess,” Whit said, “and my eyes just seemed to pick you out to look at all by themselves. But I don’t think they made a mistake, do you?”

This was the beginning of a friendship. That it was a friendship Annabelle treated rather casually did not trouble Whit. It didn’t matter that she considered him more a plaything than a playmate. Whit loved Annabelle—her beauty enchanted him—and he became her magic mirror on the wall. A child of wealthy and socially prominent parents, this goddess and her three brothers and three sisters dwelt with those parents and a grandmother, attended by a staff of nurses and servants, in a splendid mansion surrounded by spacious grounds not half a mile from Whit’s home. He often was invited there to play. One day he discovered a large collection of classical and semi-classical records in the cabinet of an expensive phonograph. He was given permission to play the records and sometimes would sit for hours listening raptly, until the patience of Annabelle was taxed beyond endurance.

Annabelle’s mother, however, was more indulgent and greatly amused by his absorbed listening. One afternoon she asked Whit why it was the music fascinated him so much.

“It’s because I like the colors,” Whit shyly replied.

This answer visibly astonished Annabelle’s parent, who looked at Whit sharply. “You what?”

Whit was mildly frightened, suddenly ill at ease. To him it was a natural enough phenomenon—he heard music and he “saw” colors. Only there was a greater intimacy, a more perfect oneness. In a way he couldn’t possibly explain, music was color.

Whit explained all this as best he could. When his young friend’s parent still did not seem to understand, and voiced the hint of a suspicion Whit was trying to make her the butt of some childish joke, he went to the piano and demonstrated, picking out with two fingers melodic fragments of a work he especially enjoyed.

“Don’t you see the colors?” he asked hopefully. “Don’t you see them now?”

Still Annabelle’s mother did not see, but this suddenly was not important. For it had dawned on Whit what he had done—he had played the piano and he didn’t know how!

That evening at the supper table he excitedly recounted the events of the afternoon.

Hallie listened attentively, letting Whit talk himself out. Then she put several preliminary questions to her son before asking, “Would you like to take piano lessons, Whit?”

Whit’s answer was an enthusiastic yes.

For Whit, learning to read music was no chore. He raced through his lessons, striding with seven-league boots toward an ultimate, toward the day when he might have his own say. He didn’t try to explain his paradoxically disciplined impatience, not even to himself. What mattered and what motivated him was the fact that there was something inside him and it did not belong to him; it was good and warm and bright and he knew that he must somehow find a way to articulate it, let it flow out of him.

Whit’s teacher soon became enthusiastic over her peculiar pupil. She marked him as one whose future held bright promise of a musical career. He was such an odd little boy, so sure of himself, so friendly, so polite, so anxious to become a perfectionist according to his own estimate of perfection.

Whit remained, as well, a human little boy, not above cutting short a practice period to go out and play.

The spring of the year turned to summer and school was out for the annual vacation period. Whit tramped his beloved hills alone. He joined in the games of his many friends. He went to the city with his mother or to a ball game with his dad. He rode the racing bike his father had bought for him.

One summer day he returned home tired and feverish. That day and for several preceding days he had been building a cave with two pals near a creek. He had been stung several times by mosquitoes but had paid the bites no heed. That night his condition worsened; his fever rose. A lethargy settled upon him. A doctor was hastily summoned and at first thought Whit was suffering from the flu. That diagnosis was later changed—and changed, too, was the whole course and pattern of Whit’s life.

Whit had been attacked by encephalitis. The disease apparently destroyed, literally ate away, that portion of his brain which gave him his tonal sense. He was left tone deaf. Except mechanically, he was never able to play again. He never tried. Gone were the beautiful colors, the lively, wonderful colors, the friendly colors; left behind was a murky residue, gray, inanimate, dead.

This disease ravaged Whit’s personality as well as his physical self. As a consequence, he became a quiet, brooding child. His sense of loss was so great and so personal, and the wound it inflicted so raw and so ugly, that the only protection he had was to embrace the fiction that what had happened didn’t matter, was of no consequence. His external world surrounded Whit with cruel contradictions and those contradictions, in turn, caused internal conflicts which he was able neither to resolve nor accept.

If reprimanded in school for some minor infraction, Whit would burst into tears, or explode into a tantrum of temper. Once, irrationally angered, he climbed through an open window of the school on a Saturday morning and wrote an unexpurgated opinion of one of his teachers on the blackboard. He did this because the teacher had wrongly accused him of something he hadn’t done, and had lectured him in front of the class.

As well, Whit manifested a cruel streak, directing it particularly against those he loved best. On one occasion his parents saw him kick the family’s fat little dog Tippy when she came running to meet him, joyously wagging her stumpy tail. Scolded by his dad, Whit sobbed and ran, with Tippy loyally running after him. He ran until he dropped from exhaustion, falling in a heap, convulsed with sobs.

Tippy watched Whit piteously. She whined to draw his attention. He called to her; without hesitation, the little dog ran to him, licking his tear-stained face and wagging her stump of a tail.

“Tippy,” Whit cried, “something’s wrong with me! I do things I don’t want to do but I can’t keep from doing them!”

Whit didn’t understand. He didn’t understand that he desperately needed love and yet felt he didn’t deserve it. The cruelty was sign language; it was the only way he had of asking for help and still not knowing he was asking. Too, the cruelty expressed the conflict inside him, and the unhealthy need for “enemies” that conflict created.

A few days after he had kicked Tippy, Whit was swinging aimlessly, in wide, vicious arcs, a huge bullwhip another youngster had loaned him and which his father had ordered him to give back. He was playing close to their garage when his mother unwittingly stepped from the garage directly into the path of the whip. Hallie was struck and knocked to the ground. Her cry brought Serl on the run. Whit’s dad took one horrified glance at his wife writhing on the ground, saw Whit still holding the whip and concluded his son had deliberately struck his mother. In a rage, Serl snatched the whip and began striking his son with it. His wife’s protesting cries finally brought the father to his senses.

As the whip bit into him, Whit stood perfectly still; he uttered no word, made no effort to ward off the attack. Actually, he had not known his parents had been in the garage or even at home when he had returned from a neighbor’s and had begun to play with the whip. When his father abruptly stopped striking him, he looked once at his mother, and his shame and confusion became so overwhelming that he ran and hid himself and implored God to strike him dead.

Much later, near midnight, with the faithful Tippy’s help, his mother found him. She took him in her arms, shut off his bitter words of self-reproach and assured him over and over that she and his father knew he had not struck her purposely.

In days after this incident, Whit withdrew completely into himself. He would shut himself in his room and for hours at a tim

e sketch frightening scenes depicting the terrible fear festering within him. Whit was afraid of himself, certain that God had become displeased and angered with him. The world for him had become a strange and sinister place and he felt, for reasons he could not fathom, that Providence had given him a once strong body only so it could be ravaged by sickness and disease, two hands only so they could be used to inflict pain, and special talents only so they could, one by one, be snatched away from him. He believed sincerely, then, that he should never hope to be anything but a sickly, obscure little boy; if he remained such a little boy, he would bring no further misery and heartache into his parents’ and his own life.

This was why he softly gave for reply a simple “no” when his dad later asked him if he would like to take art lessons. Earlier, without his knowledge, his parents had taken some of his drawings to a doctor and then to a psychologist and had been advised, after the doctor had had a talk with Whit, that these lessons might give him an opportunity to work out of his mind the irrational horror gripping it and, since his sketches revealed a natural aptitude, might also compensate for the loss of his music.

Whit did not and could not explain to his mother and father his fear that if he should become an artist God might contrive to cut off his hands. He did not and could not explain that he was afraid of his hands because they once had held a whip and inflicted pain. And where his sketches at first showed considerable skill, they became clumsy, crude scratchings after the offer of art lessons.

It is not in the nature of the young, however, to remain in the company of terror when flight is open to them. Time and his parents’ loving care eventually blunted Whit’s fears and, with the passing months, his life again assumed a reasonably normal, reasonably happy pattern. The family unit had remained tightly knit. Whit’s dad continued to do well with his work, so there were no financial cares. And he himself continued to do excellently in school. Yet Whit, better than anyone, sensed he was simply marking time. He knew that colorless anonymity, when the time came, would offer no protection against what he was certain awaited him. He was a lad whom fate had not treated kindly, and he found it impossible to ignore, to stifle the creative urge inside himself.

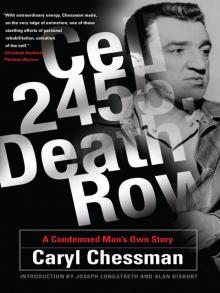

Cell 2455, Death Row

Cell 2455, Death Row